After several years of discussion among faculty across MIT, with support from the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (SHASS) and the MIT-Arab World program, MIT Global Languages announced the launch of a pilot of Arabic. IAP 2022 subject offerings include 21G.951 Arabic I, followed by 21G.952 Arabic II offered in the spring, both taught by Dr. Greg Halaby.

Global Languages Director, Professor Emma J. Teng, noted “We are very excited to finally be able to offer Arabic. We have had long-term demand from students for Arabic, and until now MIT students have had to enroll at Harvard or Wellesley to study this language for credit.” She explained that the new pilot was made possible with the support of the Arabic Alumni Association.

The language classes will bolster other subject offerings about the Middle East at the Institute. MIT offers a Middle Eastern Studies Concentration and a minor in SHASS, designed for students interested principally in the art and architecture, culture, economics, history, and politics of the Arab world, Iran, Israel, and Turkey. The Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture (AKPIA) at MIT is an international graduate program that aims to promote, sustain, and increase the teaching of architecture of the Islamic world, preparing students for careers in research, design, and teaching.

Ford International Professor of History and Associate Provost Philip S. Khoury, who serves as the faculty advisor for Middle Eastern Studies, pointed out “The new Arabic language pilot will help to prepare MIT students to better understand and engage with Arab culture and society.”

Nasser Rabbat, Aga Khan Professor in the Department of Architecture and the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture, explained the significance of offering Arabic. “Arabic is the national language of 22 countries and the mother tongue of more than 400 million people. It is also the language of the Qur’an, recited in the original language by the world’s 1.5 billion Muslims. Arabic has also been the primary language of literature, science, philosophy, law, and liturgy in the entire Islamic world until the 20th century. It is one of the six official languages of the United Nations today.”

Richard Nielsen, Associate Professor of Political Science, is a scholar who uses computational methods to analyze Arabic texts. He said, “I’m excited for students to encounter the beauty and complexity of this language and bring this into their studies in engineering, science, the humanities, and the arts in all parts of the Institute.”

His enthusiasm was echoed by Sulafa Zidani, an Assistant Professor in Comparative Media Studies/Writing, a scholar of digital culture who has written on Arabic memes. She pointed out “Learning Arabic will grant students a new perspective on the world. While learning the grammar and syntax, they will be gaining access to history, poetry, popular culture, and food spanning across countries with Arab and Muslim majorities as well as the diaspora.”

MIT engagements in Middle East

MIT’s engagements in the Middle East go beyond class offerings. MIT has had a range of global engagements with the Arab-speaking world over the years. The MIT-Arab World Program, launched in 2014, was created to strengthen ties between MIT and countries of this region. The program offers opportunities for MIT students and faculty to engage and collaborate with peers in the region, including internships, the Global Teaching Labs program, and Middle East Entrepreneurs of Tomorrow (MEET), which takes MIT students to Jerusalem to teach computer science and entrepreneurship to young Israelis and Palestinians. The MIT Ibn Khaldun Fellowship for Saudi Arabian Women, founded in 2009, has brought over 42 Saudi Arabian women PhDs to campus to further their professional development in science and engineering.

A new book, Design to Live: Everyday Inventions from a Refugee Camp (MIT Press, 2021), co-edited by Prof. Azra Aksamija (School of Architecture and Planning), features the work of an MIT-based team that worked with Syrian refugees on design projects, highlighting their inventiveness and creativity. The MIT-Jordan Abdul Hameed Shoman Foundation Seed Fund provides grant opportunities to both Jordanian and MIT faculty pursuing research in a wide range of fields from environmental engineering and water resource management, to Arabic language automation and food security and sustainable agriculture.

In the words of Prof. Rabbat, “Teaching Arabic at MIT will not just be a recognition of its long and glorious history, but also an acknowledgement of its enduring relevance to our increasingly networked and transcultured world today.”

Arabic calligraphy event celebrates pilot launch

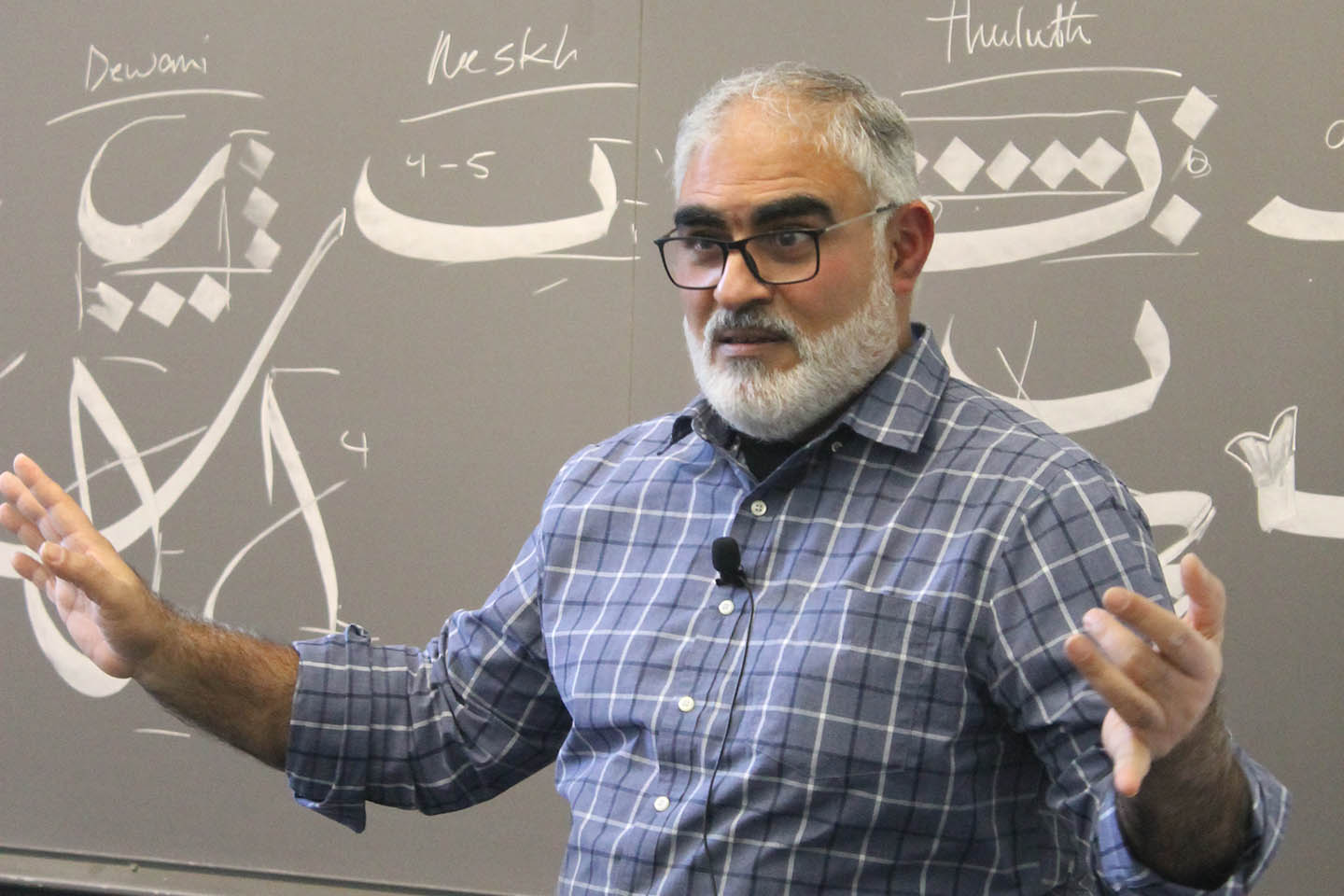

At a December 9 event, MIT students, some of whom may be more familiar with a laptop than pen and ink, had the opportunity to learn about the history and art of Arabic calligraphy from a local master, Hajj Wafaa. Mr. Wafaa is a freelance calligrapher who has taught Arabic calligraphy in the Boston area since 2004.

The event was held to celebrate the launch of the Arabic language classes and was cosponsored by MIT Global Languages and MIT-Arab World. Joyce Roberge, Global Languages Undergraduate Academic Administrator, moderated the event and announced the new Arabic language offerings.

Originally from Kufa, Iraq, Mr. Wafaa found himself a refugee in Rafha, Saudi Arabia in 1991, where he taught himself calligraphy using paper, ink, and tools of his own making. His presentation described how Arabic calligraphy developed across time and geography and he demonstrated the characteristics of the various styles. He also introduced the audience to the basic implements and materials for calligraphy, describing how refugees used found materials to make pens, ink and paper. Mr. Wafaa showed slides of some of his own creations, and made suggestions for students interested in becoming practitioners. He also explained some of the differences between Arabic and Chinese, Japanese, and Latin calligraphy. After his talk, he put pen to paper to write students’ names or chosen words in Arabic calligraphy. A station was also set up with materials for students to try their own hands.

When asked if the global prevalence of computers will destroy the calligraphic tradition, Mr. Waafa explained that calligraphy is not a mere tool for communication, but rather a profound practice of culture and tradition that continues to attract students to the discipline and artistic expression.