Anjali Nambrath traveled to Paris for two weeks with MIT’s January Scholars in France (JSF) program this past IAP. Nambrath is a Physics major, class of 2021, and a French minor. She shared with us the following first-hand observations of Paris’s protests.

By Anjali Nambrath

France is a remarkably centralized country, and Paris has historically been its capital politically, financially, artistically, and industrially. It doesn’t require a leap of the imagination to understand why it has also become a nexus for social movements in France. France has had a long and storied history of populism and revolution, of protests and strikes, of dissidence and debate – and the present is by no means an exception. But I was truly unprepared for the pervasiveness of this culture in Paris. We had been informed beforehand that there would be massive strikes in the city, protesting proposed reforms to the retirement system, and indeed there were. But there was equally evidence of an entire ecosystem of protest.

The retirement reform protests are the first that come to mind, because nearly all of the city’s metro workers had gone on strike for the first week that we were there. Metal grilles barred the entrances to the metro stations, and the wait time displays at bus stops were simply blank. We had to download a new transit app in order to account for which lines were open every day, and for Parisians it seems that checking for news of the strikes was as routine as checking the weather each morning. The strikes have been happening in Paris for months now, in response to a proposed change that would raise the retirement age and require workers to have saved a certain amount of money before retiring. France’s largest unions have turned out in protest, and large swaths of Paris were crippled by strikes across a multitude of sectors.

On one of the first days, we took some slightly circuitous routes in order to avoid a huge protest that was happening in the Place de la République. We could hear shouting and loud music from a few streets away. Afterwards, videos and photos showed that the protest had later become violent, with police using tear gas and protesters breaking windows and throwing projectiles. Two days later, I found myself again in the Place de la République – along with people taking their dogs for walks and pushing strollers on clean and peaceful streets, with no sign of the earlier events.

Some days later, while on a bus, I passed a large protest in front of the Panthéon and the Sorbonne. I hopped off at the next stop, which was surrounded by a line of police vans and a small huddle of armed Parisian policemen, presumably there in case the protest got violent. Unlike the earlier one, this protest had been organized by a smaller union of education professionals in solidarity with that day’s main protests. I ended up near the main events later that day, which were in the neighborhood of Les Invalides and the Champ de Mars. The streets there are narrow and when I arrived they were totally blocked, either by massive bottlenecked traffic jams or lines of riot police vans (belonging to the national police this time). Later that day, I walked to the Champs-Élysées, where there was another huge line of Parisian police vans and no sign of protesters. I never got near the protests themselves, but the level of police presence all over the city was truly striking. There’s an interesting contrast between the hypervigilance of the French police and relative nonchalance of actual Parisians who were still going about their daily business.

The police presence does seem to be something that has left an indelible impact on people, and not without reason. The French media is full of accounts of gratuitous police violence towards protesters, describing incidents where people were randomly tripped, kicked, and beaten by police officers. Within the last year, eighteen protesters lost an eye, four lost hands, and three fell into comas after sustaining brain injuries at the hands of the police. There has been an outpouring of criticism towards the police from many directions. Street artists have amplified that criticism by painting cartoonish, overturned police cars on the upper parts of high walls all over Paris – one of many graffiti motifs which are visible all over Paris, but one of the few with a societal message. Each painting is an artist’s testament to the turbulent protests which have rocked France over the past year and a condemnation of the police violence that has accompanied it.

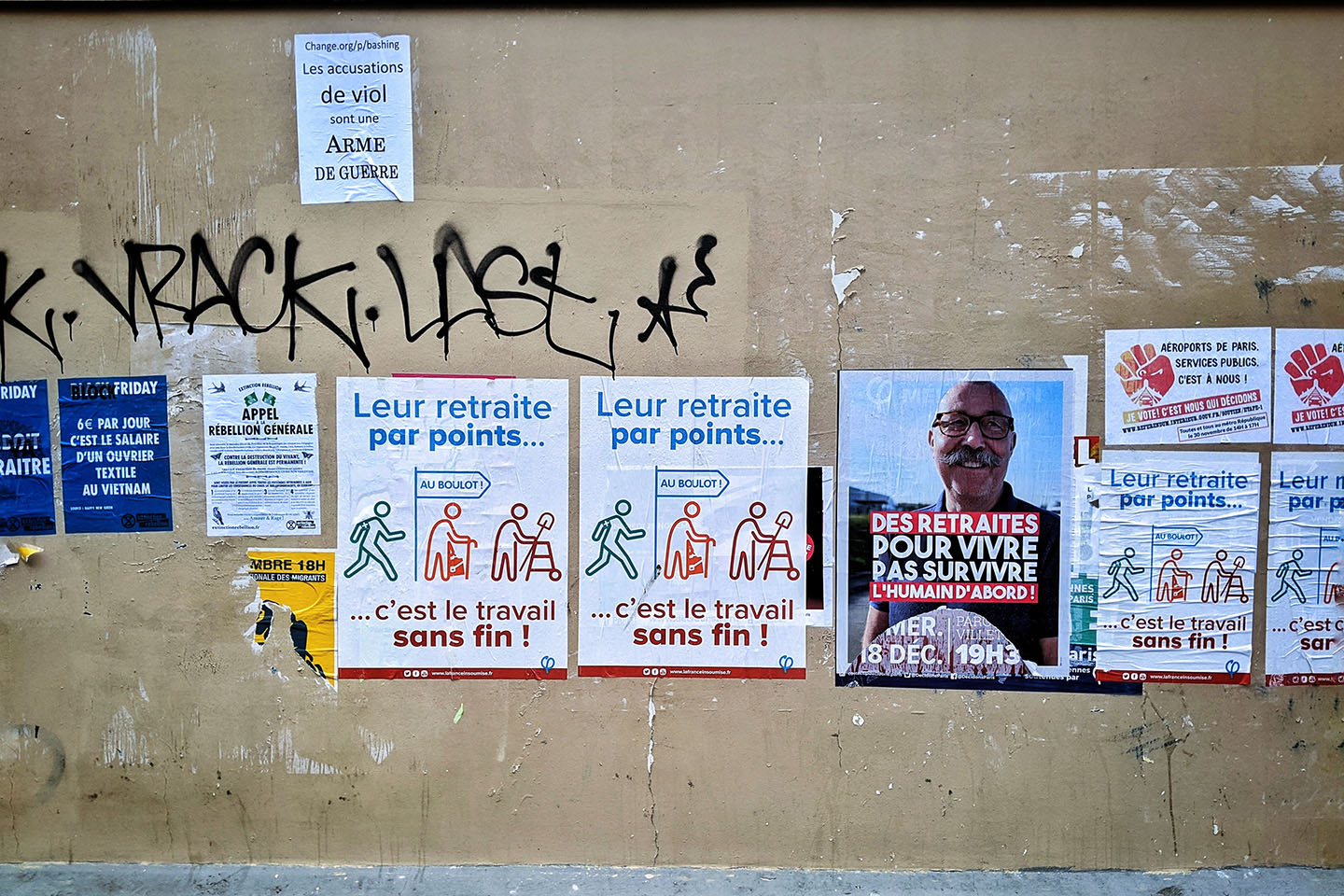

But there are plenty of other movements whose advertisements and posters cover the walls of the city. In Belleville, a solidly working-class and immigrant neighborhood, one wall alone was papered with posters for solidarity with Kurds in Turkey, for a referendum to stop the privatization of French airports, for a movement against detention centers for illegal immigrants, and for various left-leaning parties in light of the retirement reforms (including the French Communist party and the Anarchist Federation). Another movement with a visible presence across the city is a decentralized organization of women seeking to raise awareness of the government’s inaction on domestic violence and femicide. Each poster of theirs is a simple affair of black paint on white paper, but the messages are truly powerful. Sharing statistics, personal stories, and a general feeling of frustration and anger towards the government, the posters communicate the reality of life for too many French women.

Many of these movements have been promulgated by left-leaning organizations and institutions in France, but the left does not by any means have the chokehold on organizing and mobilizing in France. The day before I left Paris, I was walking through the Place de la Concorde in the midst of a massive traffic jam. Cars were essentially stuck in place around the massive roundabout, and scooters and pedestrians wove arbitrarily through the lanes of traffic (including one woman resolutely leading a group of elementary schoolers through the mass of vehicles). I thought the reason for the traffic was another one of the myriad retirement reform strikes, but when I googled it later it was entirely something else. Over 40,000 people from all over France had descended on Paris for a protest against a proposed law that would allow all women to receive artificial insemination or in vitro fertilization treatment. The protesters were carrying placards and chanting slogans about the importance of fathers in children’s lives, and in interviews some cited the “negative” effects of marriage equality and minority rights as reasons for the protest.

Paris has been and is the terrain of choice for popular movements throughout French history, because it is the only place where French people can confront all the powerful interests of their country at once. The city has been visibly marked by the protests of its past and continues to be affected by those of today, whether it’s the physical toll of protests on shop fronts and city infrastructure, heightened police presence and police violence, street art and political messaging, or simply vivid posters on walls.

MIT’s January Scholars in France program brings a select number of MIT undergraduates to Paris during IAP for two weeks of cultural and linguistic immersion, led by MIT instructors. Airfare, lodging, guided tours, and field trips costs are covered by MIT. Preference is given to French majors, minors and concentrators, and those with a demonstrated commitment to French Studies at MIT. Information about the 2021 trip, and how to apply, will be available in Summer/Fall 2020.